Before I delve into what this blog is really about, an introduction to explain the title of this entry is in order. The relationship between the title and the subject matter of this blog will become clear later on.

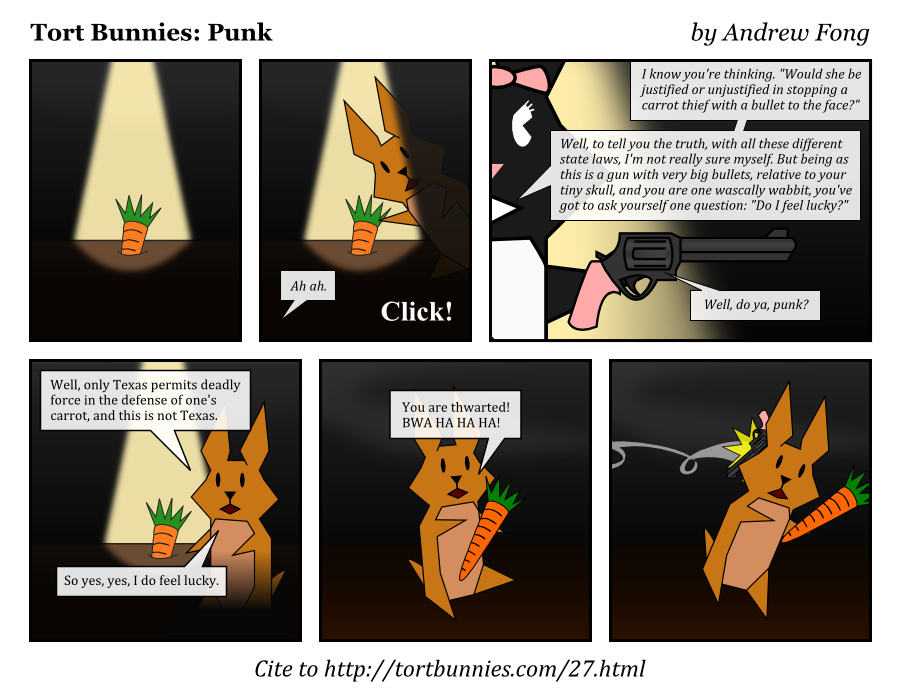

So what is Tort Bunnies you ask? Tort Bunnies is a website created by a law student named Andrew Fong. It showcases original comic strips made by him featuring a character named Tort Bunny, a female bunny in the habit of battering her friends, or in the words of Andrew, of inflicting upon her fellow bunnies "intentional harmful contact." His comics present U.S. and common law concepts in a format that is easily digestible and funny. For instance, check out the strip below:

Note: The image above does not belong to me. No copyright infringement intended. All rights revert back to the owner.As I was perusing his website, I came across his 29 March 2010 panel (see above) and its accompanying note. The opening sentence of the fourth paragraph reads: "Two other things: First, Tort Bunnies is now accessible to the blind." This statement naturally piqued my curiosity. First, why would a blind person be interested in a site that relies heavily on images to convey its product. Second, considering that his comic strips are in the form of images, how did he manage to make them accessible to the blind? Third, even if there was a way to make the images accessible to the blind, what drove him to make this move? Upon closer inspection, I found the answers to one and two. He embedded the transcripts (click here for a sample) of his panels to his website, such that, with the help of a screen reader, a visually-impaired person will be able to appreciate the panels by hearing their spoken version. But what led him to make his website accessible to the blind? An even deeper investigation yielded the answer. Apparently, a classroom discussion inspired him, specifically, a debate on whether or not Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act can be made to extend to websites.

Under Title III, no individual may be discriminated against on the basis of disability with regard to the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, or accommodations of any place of public accommodation by any person who owns, leases, or operates a place of public accommodation. Put differently, a person who owns, leases, or operates a place of public accommodation is mandated by law to make accessible to disabled persons the full and equal enjoyment of goods, services, facilities, or accommodations offered by the public accommodation. A website, though not representative of a physical space, is arguably a "public accommodation" because it is a (virtual) place accessible by the public.

My opinion is that a website should be considered a "public accommodation." First, the law does not distinguish between physical and virtual spaces. Second, just like physical spaces, cyberspace is now used as an avenue to offer, sell, and distribute "goods, services, facilities, or accommodations" to the general public. However, I do not think that all websites should be made to fall under Title III. But before I go into which websites should be excluded from the list, let me first identify which websites must be accessible to disabled persons: government websites that serve as gateways to basic services for the simple reason that citizens (disabled or not) are entitled to the care and protection of the government. Now that that is settled, let me get into the thornier issue of which websites should not fall under Title III.

Note: This is Part 1 of a two-part series. Part 2 will be posted next week.

--Jan Nicklaus S. Bunag, Entry No. 8

No comments:

Post a Comment